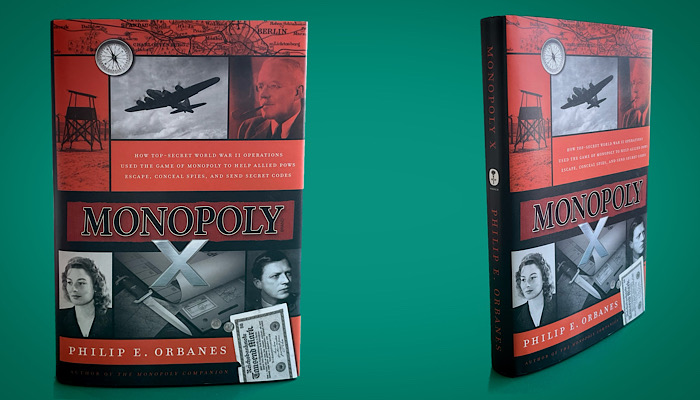

Mr. Monopoly – Philip E. Orbanes – discusses the extraordinary secrets within his new book: Monopoly X

Fantastic to see you, Phil. We’ve wanted to interview you for ages… And now seems like the perfect time with your new Monopoly book coming out. It’s on a topic that I just find fascinating! What’s the name of the book? And the enormously descriptive subtitle?

Well, the name of the book is Monopoly X – and the subtitle is, ‘How top-secret World War II operations used the game of Monopoly to help allied POWs escape, conceal spies and send secret codes.’

I love it! Tell us about it!

It’s all about the big, largely unknown role that Monopoly played in the war. It’s actually a very UK centric book because while the US had a very important role as the war went on, a lot of the war rested on the UK. So! The Monopoly X story involves Waddingtons and Waddingtons Games in Leeds. As you know, they were the manufacturer of Monopoly in England – and they had a huge impact on prisoner activity on the continent, especially involving the escape lines.

This remarkable story all began, really, with a marvellously eccentric former magician named Christopher William Clayton Hutton. He was part of MI9 – a satellite of MI6… MI6, as you know, is the UK’s foreign spy organisation. But MI9 was set up with one specific purpose: to help British soldiers and airmen trapped on the continent escape back to England.

Right!

For the most part, of course, that meant getting them out of the Prisoner of War camps. But it also involved helping downed airmen who were on the run, or trapped in France and Germany. So Clayton Hutton’s job was to devise evasion and escape aids to help people. And just about the first thing he needed to do was to come up with reliable maps…

Maps of enemy terrain?

Exactly. Because if you’re an airman, parachuted into France, you’ve got to figure out where you are and which direction to go in to get home! Either on your own or after you hooked up with a member of an escape line. I’m going to show you an actual escape map now…

My days! This is this an original? It’s not a replica?

It’s original, yes – and you’ll notice it’s not made of paper… It’s made of silk. The reasons for that are that – number one – silk, when you fold it, doesn’t deteriorate on the fold lines. Two, if it gets wet, it doesn’t fall apart. And three: it’s silent! If you’re in the woods at night and you unfold a paper map, you’re going to make a sound… Just that little noise could be a dead giveaway to those looking for you.

So… Clayton Hutton knew he had to make his maps on silk – and there was one company in the UK that already specialised in printing on silk. That was the John Waddington Printing Company in Leeds. They just happened to also be in the game business – and they made Monopoly. So MI9 asked Waddingtons to secretly provide the silk maps that were sewn into the uniforms of every British airman! After that, Clayton Hutton realised that he somehow had to get these maps into POW camps, along with other escape tools, without the Nazi guards finding them. And he put two and two together!

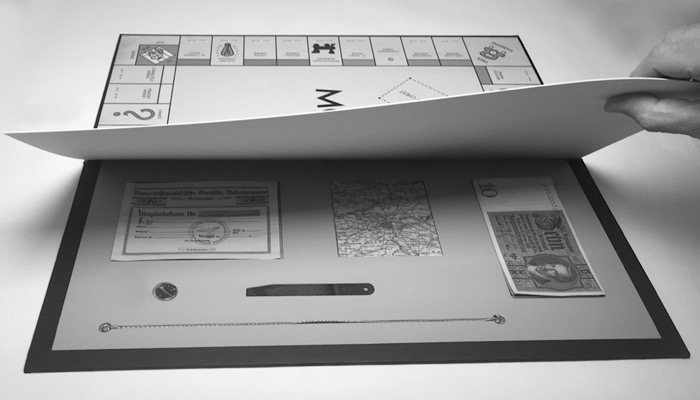

Amazing! So that map you’re holding folds up and fits into a Monopoly game board?

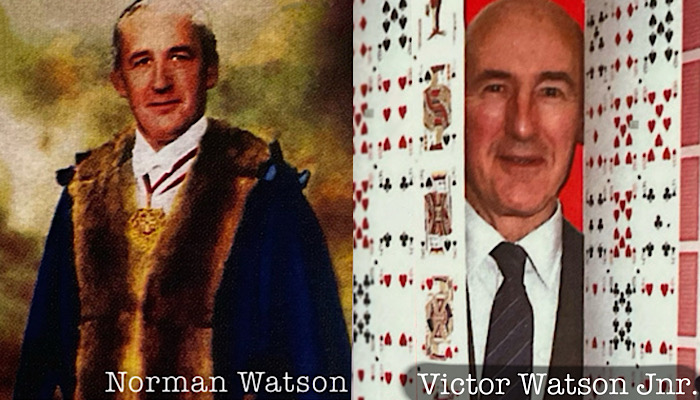

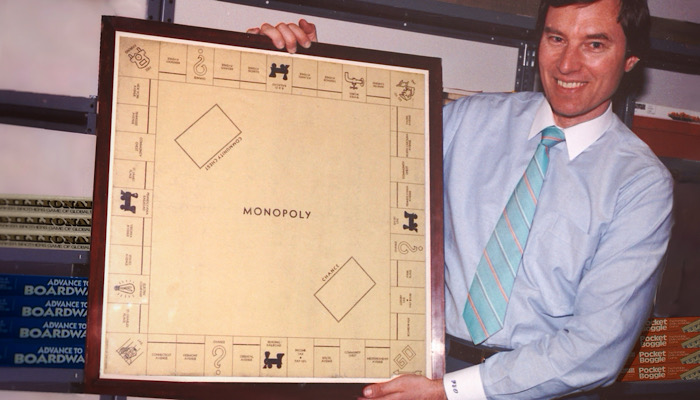

Yes. I have a replica of one of the boards here… You can see that this looks like a typical Monopoly game board from 1943. I made this replica based on instructions given to me by Victor Watson. Victor was the chairman of Waddingtons for many, many years. He was also the son of Norman Watson, who is such an important figure in Monopoly X because he was the chairman of Waddingtons during the war.

As you can see, it looks just like a regular Monopoly game board… But if I lift the paper surface, the label, you can see these built-in compartments. Everything that goes in them sits flush. That way, when this board arrived in a POW camp, it would pass inspection by the Nazi guards, Then, all the prisoner had to do was rip off the label to get a whole slew of escape aids.

This is amazing. Just before we get to the contents, Phil, let me ask… To the best of our knowledge, did the Nazis ever detect this?

No, they never did. It was used extensively during the war by both MI9 and the American equivalent, MIS-X. Part of the reason that the Nazis never caught on is that, after a POW extracted the equipment, they burnt the board. That was the most important thing because if anybody discovered the secrets of the game board, the gig would be up.

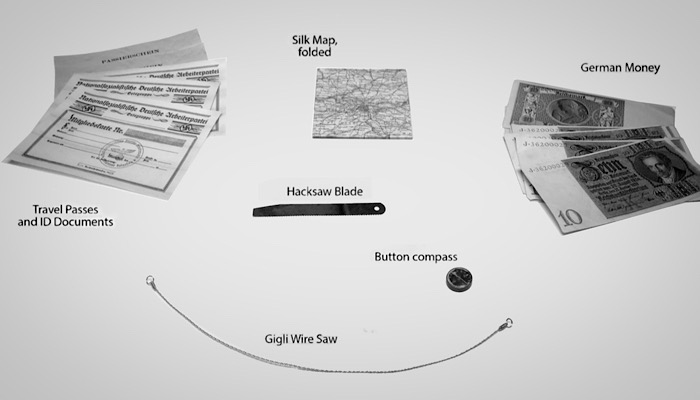

Perfect. So what are some of the things that POWs might’ve found in those compartments?

First, these are German documents that would let you move about more freely after you’d escaped. Then – and this is one of most important things – German money. Realistically, your first objective after escaping was to get to a train station, buy a ticket, and get the hell out of the area. You had about four hours to get further away from the POW camp… If you could do that, it made it much more difficult for the Nazis to find you.

Right. Just the paperwork and the money would be a tremendous advantage…

And this this is a razor blade! It’s magnetised, so it points north; it acts like a compass. They could also conceal real compasses that were about the diameter of my finger! Also, they had hacksaw blades in the board. All you had to do with one of those was attach a wooden handle to it. And then this, I think, was extremely ingenious… It’s not something that most people know; it’s called a Gigli saw: G,I,G,L,I.

This is a new one on me, Phil! What’s a Gigli saw?

It’s a serrated piece of wire. If you attach handles on either end, it becomes an effective saw. A POW could use it to saw through metal bars, but – originally –surgeons used them to saw through bones.

Oh, wow! Perhaps you could clear something up for me, Phil… As well as concealing things within the board itself, would the secret services hide anything in the money or playing pieces?

Ah! No! That’s a myth… As a matter of fact, it’s a myth that I inadvertently helped spread before I knew better! The reason being that, when you open a game of Monopoly, you encounter this board straight away – and it’s so cleverly made that it would withstand some scrutiny. If you looked at all the components, though, they were very easy to rifle through! It would be fairly easy to see if there was anything in there that didn’t belong.

Thank you! It’s been bothering me because I’ve been told a few times that there was real money hidden in the fake money… That didn’t quite add up to me, because – as you say – you’d only have to flick through that money to spot something very recognisably real…

Right. There was no way they could’ve put anything in with the components; it all had to be hidden inside the game board. Another thing that Clayton Hudson really liked about the Monopoly board was that it was large… That meant they could fit a lot of these little lightweight items in there. Now, MI9 did use other items to hide things: shaving brushes, gramophone records, cribbage boards… All sorts of creative things. But, over the course of time, a lot of those were discovered…

Of course, once you discover that someone has used ONE hollowed-out shaving brush to smuggle something, you’re going to check every shaving brush! So, eventually, you’re only down to items that the Nazis wouldn’t inspect.

Well, on that, Phil… Why do you think the Nazis paid less attention to the Monopoly boards?

That’s a good question. One reason is, I think, because Germany is a game-playing culture. They take games seriously, and they probably imagined that game playing would take the POWs’ minds off escaping… It would’ve seemed like a worthwhile diversion. So they encouraged the games, not knowing that they were inadvertently providing resources for escape attempts.

You mentioned earlier that this ruse was quite a prolific one… I have two questions from that. First, do you have any idea how prolific?

Yes… In the book, I point out that – during the course of the war – there were, based on extrapolating British records from POW camps, about 11,000 POWs that escaped from camps. Of those, a little more than one in ten actually made it back to England.

Astonishing, really…

But the important thing about the escapes, and the reason they were constantly encouraged from London and Washington, is that if a POW escaped, it diverted a lot of the Nazi resources. They had to mobilize to try to find the POW and return him to the camp. So it was it was very valuable to escape – even if you were recaptured.

Yes, I understood that it was almost your duty to cause disruption by trying to escape…

By the way, all that was condoned by the Geneva Convention. Unfortunately, Hitler decided – toward the end of 1944 – that the escapes were too big a problem. He issued an an edict, which was quite alarming to the Luftwaffe in particular, that any POW who was caught escaping would be executed. That still didn’t deter escapers…

Wow… No, I imagine it would still feel like an objective if not an obligation to do it. And I appreciate that you’ve very faithfully recreated the board there, Phil, but it leads to an obvious question to which I’ve not yet had a definitive answer! Did any of the actual boards survive?

Ah! Not that we know of, no. And this is another thing that’s both amazing and maddening… The Monopoly project worked so well that it remained a secret for decades. At the end of the war, the UK and US governments ordered the two escape organisations – MI9 and MIS-X – to burn everything! Destroy all evidence of these things…

So much history up in flames!

Which is understandable because, of course, the reason was the great fear that the Allies would still need to use the things that worked if the Soviet Union overran Western Europe… So the powers that be decided not to share the secret, or spoil it by bragging. And all the records were destroyed. All of the extant games, for example, were burned… I have documentation to prove that. As a result of that, there’s very little that you can find in the archives.

That being the case, Phil, what are your sources?

Well, fortunately, there were some people who lived through it all who, in time, were able to talk about it. But even if you read, for example, Christopher Clayton Hutton’s book – which he happened to name Official Secrets Act – you’ll see it’s heavily censored. And that’s because the secret was fully maintained about Monopoly in particular for forty years… Not till 1985 did people start to hear about it.

And where were you in 1985?!

In 1985, I’d been working at Parker Brothers for six years. I’d served as the chief judge at the World Monopoly Championships almost from my arrival… But that was really because I was the only one who knew the game. I mean, it had marketing behind it and R&D, but nobody ever really paid much attention to the strategy, tactics, or history of Monopoly until I got there! And that’s how I met Victor Watson, the son of Norman Watson, who was the man who did all the war-related projects at Waddingtons.

And it’s worth mentioning, Phil, that I spoke to Victor Watson’s family about the history of Waddingtons Games around a year ago. People can read that here. And Maggie Graham – with whom I believe you correspond – did an interview about the war effort here… But how did you come to know Victor?

Victor was the brains behind the first Monopoly Championship in 1973. It worked so well that Parker Brothers and Waddingtons decided to hold them periodically. So! I met Victor in 1980… As a result of this, we became good friends. Later, in the summer of 1985, Victor came to Parker Brothers in Massachusetts to have his annual business meeting. I remember it very clearly! He was very animated with excitement, and he said to the president of the company – who was a good friend; a mutual friend: “You won’t believe this, but I can now tell you a great secret… Monopoly was used to smuggle escape aids to POWs in World War II… And my father was the person who loaded the game boards!”

Extraordinary!

From that point on, Victor started to give me more and more information., Then, after about 2005 it really opened up as more and more official restrictions lifted. And since Victor knew the books I’d written about the history of Parker Brothers and the history of Monopoly, he decided he wanted me to publish this story… The stuff that his father had passed along to him but could never talk about.

Of which: Maggie Graham mentioned that parts of the Waddingtons factory did other things for the war… What do you know about that?

Well, beyond Games, Waddingtons was a versatile printing firm. They innovated wax-covered packaging, for example, in which one could sell milk and juice. During the war, that technology was used by ICI Metals to package flares. Again Waddingtons did that in utter secret! They were making these these dangerous flares for ICI one part of the factory, and the people who were working on the silk maps had no knowledge of that… Norman Watson had to keep them all separate.

One other thing was that the British Treasury contemplated melting down all the coinage in circulation so that they could get more metal for various war productions. Here again they turned to Waddingtons to print paper script for change. So shillings and pence were represented by not coinage, but by paper. All of that was printed by Waddingtons and stored secretly in the event they had to replace coinage.

Oh, my days! And when it was needed?

When it wasn’t needed, it was, of course, ordered to be burned. I don’t know if any of it survived… That would be fascinating if some of it did. You know Maggie or Amanda may know that.

Fascinating. Truly! So… A lot of this is a long time ago! I’m curious then, Phil… Why is now the right time for this book?

Well, in part it took a long time to do because a great deal of material belongs in the book – and I made a promise to Victor Watson that I would present it in a certain way. Victor was a real spark plug for this book… Because Victor, after he started to reveal to me his father’s secret role, said to me, “Phil, whatever you do, don’t just dribble this out little by little. Put it all together so it’s a unified story. It will make so much more impact…” So I actually had some articles ready to go that I pulled back.

When was that, roughly?

He was advising me from around 2002 to 2005. So Victor’s proviso was that he would tell me everything he knew, and I could publish it after he died. And I think that had something to do with his own promise to his father. As you know, Victor died in the February of 2015, aged 86. Shortly after – in honour of Victor – I wrote an article that looked at one aspect of the story, and I started to think about how to organise the rest of it. And when you see the book, I’m hopeful that your reaction will be, “Well, this is the way the story should have been told!”

Because you wanted it to tell it in the right way?

Exactly. I wanted it to fit together logically and flow. But that actually wasn’t easy for me! And the person who put it together – in terms of how to tell it – was Alan Hassenfeld, one of the founding family of Hasbro. Alan’s always believed in the story, and believes it belongs on the screen. Anyway, Alan called me out of the blue one day in 2018, I think. He basically said, “Phil, this is such a great story… What are you doing with it?” Because he knew from prior conversations that I had the material and was sitting on it.

I love how everything is falling into place!

And I said, “Well, Alan, it’s so coincidental… I’m working on it now but I’m struggling to figure out how to organise it.” And Alan just said, “Here’s how you do it: you start with an actual escape! You put us in in the middle of the action…”

Start with the action – like a game sizzle! But let’s talk about that… Which escape story opens the book?

The escape story that opens the book is that of the very first successful Monopoly escapee, Airey Neave. He became rather famous, actually… After he escaped from Colditz Castle, he went on to become a lawyer and a member of Parliament. Unfortunately, the IRA assassinated him just outside the House of Commons in 1979. In regard to his escape, though, he and a Dutch POW – Anthony Luteyn – got out of Colditz on the 5th of January, 1942…

When he finally got back to London – because he had actual experience – he was recruited by MI9. They asked him to run a new group which ultimately became known as Room 900 in the War Building. His job was to organise the French escape lines, get them to work together, fund them, find out what equipment they needed and shape them up because they were going to be so vital to help rescue people on the continent. And so Neave, the first Monopoly escaper, played an active role in helping other POWs escape for the entire war.

Remarkable. And in terms of Alan Hassenfeld saying this story belongs on the screen, I believe you’re making inroads into that as well, are you not?

Ah! Well, there’s a documentary in the works right now, which should be aired early next year. And the documentarians I’m in contact with – almost daily – are just as excited and fascinated by the story as I believe you are, Deej! The challenge we all face, though, is that so many of the records were destroyed at the time – and it’s such a long time after the war that almost everybody who could help us is dead!

Yes, of course! It’s hard to do a documentary when there are so few documents! And on that… Is there anything that you unearthed – during your research – that is more or less exclusively revealed in the book?

Oh, yes! Most significantly, something I learned even before I got to Parker Brothers; 1974 through ’76… I was running a little game company in New York called Gamut of Games. Gamut of Games was funded by Waldemar von Zedtwitz… He was one of the three men in the 1920s and ’30s that travelled the US and Europe popularising contract bridge…

So: keep in mind that – until Monopoly – contact bridge was the most popular game in the world. Now, Waldemar – Wally, as he was affectionately known – came from a very wealthy background and never worked a day in his life! Instead, he devoted himself to games. He was an incredible bridge, chess and backgammon player; a linguist and an etymologist… But not someone who ever had to get his hands dirty. He moved into a Park Avenue penthouse and stayed there for fifty years! And that’s where I met him because he owned the company that I’d been hired to run… I have remembered your question, Deej, I just wanted to give you some background!

Oh, take your time! I’m loving every second of this!

So every month, I’d go to Wally’s incredible penthouse where he had umpteen million dollars of masterworks on display… A Van Gogh, a Rembrandt self-portrait, El Greco… It was a bit lost on me back then: I was only 27, and I came from the country – not from wealth. I mean… I greatly admired it, but it was the lap of luxury. Anyway, after I gave Wally my monthly business report, we had dinner, played chess or backgammon or whatever, and – on this one occasion – I found out, through a little slip of his, that he played some significant role in World War II…

Well, that made sense to me because he was a former German, and from a very wealthy background… He was fluent in a couple of languages, and I felt he would’ve been of immeasurable help to the government doing interrogations, say – which, by the way, did turn out to be the case! I finally got him to reveal that. So! To your question… Is there anything in Monopoly X that is unveiled for the first time?

Yes! I got so engrossed in the story, I forgot what the question was! Ha!

Ha! Well, the answer is yes – because Wally was in very close contact with a family in France whose last name he said was Jean… Let me tell you, though: I’m convinced that was an alias because he would never tell me the real names. In any case, they were part of the French escape lines in Strasbourg. In addition, their daughter, Benoit, was a great spy. She actually ran a mission for the OSS – somewhat by accident, but that’s in my story – and she rescued notable POWs from who had escaped from their camp.

Anyway, her story came to me through Von Zedowitz purely by accident. Just one day when he was playing chess and we were talking about the war, and I was telling him that my father was in it from day one until it ended in the September of ’45. He inadvertently, I think, said to me that he was never happy with the gas rations he got in return for what he did… So I kept gently pressing him and letting him know that I was sincerely interested and respectful of what he did. And then he began to tell me of the Monopoly secret code…

Oh?!

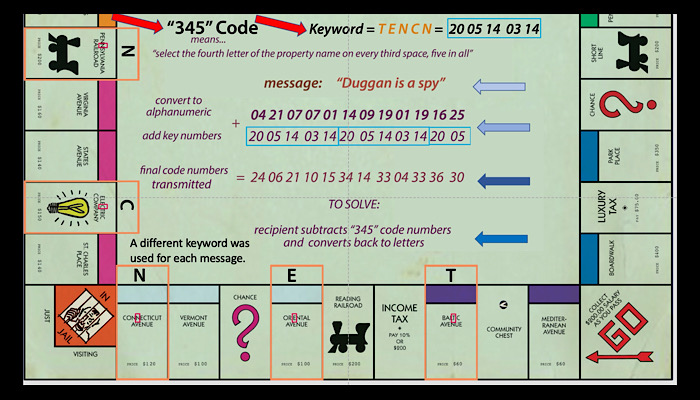

When do you look at a Monopoly board, you mainly think about the value of the properties… But of course, every single space also has a name on it. Well, it turns out that what Waldemar von Zedtwitz and his partner, Ely Culbertson, did – in order to communicate with the dissident KGB agent in Moscow – was create a coding and decoding key using the lettering on a Monopoly board…

Noooooo! Instead of a book, they used the Monopoly board to code and decode messages?

Yes. It’s easier to understand with a picture, but let me give you an example… Let’s say I sent you an encoded message and a key number: 345. That number would mean you had to open your Monopoly board and look at every third space, starting at Go. Right?

Yes… I’m writing this down!

Then you would look at the fourth letter of the property names on those spaces. And, in this example, the five is telling you to use a total of five spaces. So just knowing that you need to use the Monopoly board, and getting the digits 345, generates a string of letters…

I’m doing this in real time, so bear with me. Every third space, every fourth letter, for five letters. Well, on an American board, that gives me T, E, N, C, N.

Correct! Now you convert those letters to an alpha numeric code. By which, I mean, you work out where in the alphabet those letters sit…

Oh, my days! I feel like Alan Turing! Let me see… I’ll edit out me doing the maths! Ha! T, E, N, C, N is 20, 5, 14, 3 and 14 again. What do I win, Phil?! I feel like I’ve achieved something – but I’ve no idea what!

Well, you’re not finished yet! Ha! That’s just the key! So to encode a message, you’d take what you wanted to say and convert that into alphanumerics as well. So let’s say we wanted to say, ‘Duggan is a spy.’

I knew it! I never trusted that Duggan…

There, you’d end up with a string of numbers; two digits for each letter: 04, 21, 07, 07, 01, 14, 09, 19, 01, 19, 16, 25. But to code the message, you add those numbers you generated with the board to the digits of the coded message: 20, 05, 14, 03, 14. With the U, of course, you reach the end of the alphabet and start again at the beginning…

Oh, I seeeeeeeee! And when I get to the end of my key – because I’ve only been told to use five spaces – I start that letter chain again?

Exactly, right! I’ll send you a picture to make it clear, but ‘Duggan is a spy’ becomes 24, 06, 21, 10, 15, 34, 14, 33, 04, 33, 36 30. And without knowing the Monopoly board was the key, or having the board in front of you, it would be very hard to decode that back then. So there’s more detail about that in the book, but this was revealed to me by Waldemar von Zedtwitz way back when I was 27 – and absolutely verified in 1992… It’s just another amazing tale in the wider story.

Well, Phil, this has been absolutely fascinating! I can’t tell you how excited I am to read the book. Congratulations on that achievement – it’s been a long, long time coming. I’ll include a link to it here in the UK, and here in the US.