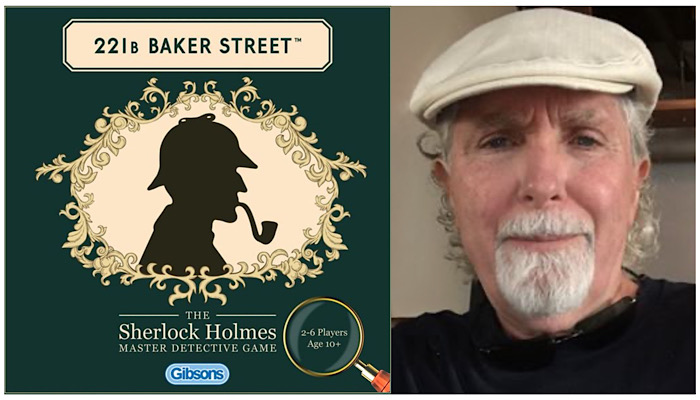

221B Baker Street inventor Jay Moriarty celebrates 50 years of his ever-popular game

Jay Moriarty! First, congratulations: 50 years of the game 221B Baker Street… That is unbelievable!

That means I’m a pretty old guy! Ha!

Ha! It certainly means you’ve got a hugely enduring game. How did it come about?

When I was in my twenties, I had a job as a copywriter. I wanted to be a writer in TV sitcoms, which I eventually became. You don’t just get straight to that, though! So not long after I left college, I did my first game which was just a spoof on planned obsolescence… It was called Beat Detroit.

‘Beat Detroit: the game that will crack you up’… It’s satirically humorous, presumably?

Right. Because Detroit’s where they make all the autos and stuff. So the idea of the game was that you got a little car at the start, and a warranty coupon that was worth nothing. If you can travel 50,000 miles round the board before you go broke or your car falls apart, you beat Detroit. That became a national bestseller… The Detroit Free Press put it on their front page, then NBC Nightly News picked it up – just in the humorous slot at the end, you know?

I do; we have the same thing here: end the news on a lighter note… And when was this, Jay?

This would be in 1972, around the time of the first major car recalls. So the game was kind of satirical in that respect… Every space you land on, something happens – except the space that said, ‘Write a letter to Detroit’ – there, nothing happens.

Ha! Nothing happens when you write a letter! Funny!

The whole thing was kind of a spoof, but it became a big seller. So I didn’t really intend to get into the game business, but – after Beat Detroit – I started getting calls asking me to do games. One of these came from a small company that wanted a detective game. I thought about it and asked myself, “Who’s the most famous detective in the world? Okay… Sherlock Holmes.” And I’d played Clue when I was a kid, obviously, and thought about the flaw in that game which is, basically, that you’re not really solving a mystery.

Right. You’re deducing which cards are in the envelope…

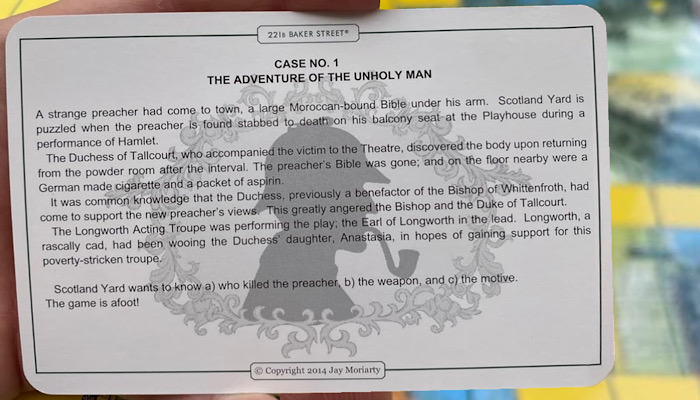

…by a process of elimination. So you know it’s Mr. Green in the ballroom with a rope. But you don’t know why! Even as a kid, I remember thinking: you never know what the motive is. So I thought about that… What if you played a game where you could actually solve a crime? Maybe it’s insurance fraud. Maybe it’s a kidnapping. Maybe it’s other stuff. I figured that if I could write a mystery that people actually get to solve, that would be a fun game. The problem is, once you solve it, it’s done!

You can’t play it again…

That being the case, I initially wrote ten mysteries before I thought maybe I should put 20 in – just in case. After that, I thought people would put the game up on the shelf and it’d all be over. 20 mysteries… More than enough!

And not to sidetrack you, but I’m just curious: Conan Doyle’s characters were in the public domain by the time you came up with the game, were they?

Yes, and I think we were the first to learn that! My IP lawyer, George Netter – rest his soul; he’s passed now – but back in the 70s, he realised that while the newer stories weren’t in the public domain, the characters themselves were. So I could use some of the fantastic Holmes characters, just not the stories. And to create the game, that’s what I did: I started getting into Holmes and understanding the characters so that I could try to be true to them…

As well as Holmes and Watson, I had Inspector Lestrade – he’s always coming to Holmes; seemingly to say hi, but then he actually wants Holmes to help him solve crimes. There’s a lot of humour there. I also drew on ‘the woman’ – Irene Adler. It was only around this time that the Moriarty thing hit me; that – just coincidentally – the bad guy’s name is James Moriarty – the same as mine.

Ha! It’s worth mentioning this because the fact that your name is James Moriarty may seem conceited… But you didn’t change your name to James Moriarty, did you? That’s your birth name…

Right. My dad was James; I’m James junior – and I had two Uncle Jims – so my mum shortened me to Jay. But my dad never said anything to me about our name being the same as Sherlock Holmes’s nemesis!

Astounding! I don’t believe in nominative determinism, but what are the chances that a man called James Moriarty would devise an all-time classic Sherlock Holmes game?!

I know; it’s bizarre! And people do tend to think I was a Sherlock Holmes fanatic since I was a kid – but I didn’t even know who Moriarty was! When people met me and heard my surname, they’d say, “Oh, the Professor!” But I didn’t know what they’re talking about. I only made that connection when I did the game, and – for that reason – didn’t put my name on the box. I put just put ‘Mysteries by James Thomson’ – Thomson being my mother’s name.

Is that because you thought it would be less confusing for people?

Yes, and I figured people would be like, “Come on, what’s your real name?” Or they’d be like, “Is that supposed to be clever?” Because it’s NOT very clever! Ha! So I didn’t do that initially. Eventually, I put my name on it for legal reasons. So now all the copyrights and trademarks are in my name in all the countries, so I don’t have to worry about any of that.

And now 221B Baker Street is 50… Why do you think the game endures, Jay?

There are a few things, but mainly two words: Sherlock Holmes. All credit to Conan Doyle… The game endures because that character endures. There’s always a TV series or a movie about Sherlock Holmes and Watson; it’s evergreen. I’ve done other games, of course, and I can expect to get three or four years out of each one new title… But 221B Baker Street is the one game that’s sustained over the years: firstly because of Holmes and secondly because it’s a good, fun game that everybody can play.

Then there’s the humour. I’m basically a comedy writer so there’s humour all through it, along with wordplay and mystery – and now nostalgia. I get people saying, “I grew up playing your game!” and so on. So it’s become popular with families even though it’s something of a thinking game. Another aspect is that there are different ways to play… You can play with rankings, you can play alone, you can play competitively, or you can play co-operatively with everyone working together to solve the case… Schools use it to teach kids deduction; Mensa groups play it. Sherlock Holmes clubs play it. I’ve spoken at a number of those.

The Holmes fans have embraced it?

Yes – I think because I try to stay true to Holmes… So I’ll take quotes from the Connan Doyle material and work them into the rules, or at the beginning of a case, say. That’s why these Holmes groups ask me to come and speak to them and, I think, part of the reason why – not long after the game first came out – I started getting calls asking how people could get new cases.

Like an expansion pack?

Exactly. In fact, one of the first calls was from some Playboy Bunnies at the Playboy Mansion. They said, “We play this all the time! It’s Hugh Hefner’s favourite game.” But I figured maybe it’s Hugh Hefner’s second-favourite game…

Ha! Yes, that would say a lot about the Playboy Mansion!

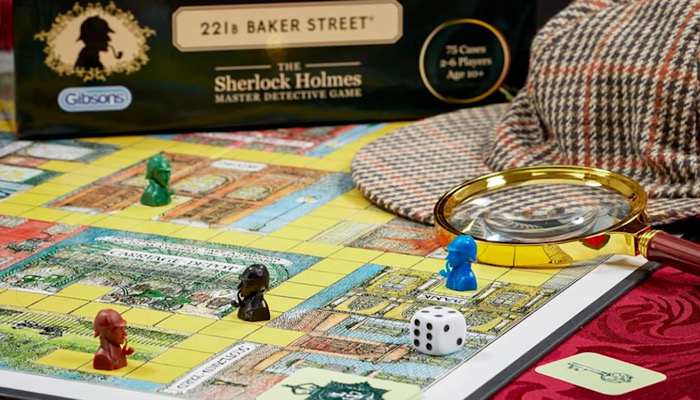

Either way, I figured I could put out a second set of cases. Long story short: over the years, the calls kept coming! By 2016, we had nine sets of 20 cases; 180 mysteries. Not too long ago, I figured I could do another 20 and put 200 in a deluxe edition, which I did… The US has a deluxe edition with a complete set of 200 mysteries. The standard 221B game that Gibsons does in the UK has 75 cases.

So what was the start of your design process? Did you come up with names for the cases, or different types of crime? Talk me through that.

Well, if you get the US game, you can look at the first five cases and see it was exactly that. I started writing a mystery case and figured there’d need to be three to five things to solve as you travel round the board, such as the killer, the weapon and the motive. But then there are different puzzles; it might be as many as five – and usually there’s some clever stuff going on… Especially, I think, in the last ten or 20 cases. A lot of like anagrams and stuff to figure out…

So there are games within the game: every time you get a clue, there’s a puzzle to figure out. That keeps the players going. And over the years, there have been variations… There was a floppy-disc computer version and also PAL and VHS video versions – like a two-hour video movie. Gibsons put it out for a bit. That sold for about two or three years when people still bought those media. We’re currently developing an app that you can play on your phone.

And how many board games have you done in total, Jay?

I did nine with my partner, who’s an artist. That gave us quite a lot of control over how things looked. But it was never my intention to be a game inventor! I grew up in Ohio. I majored in English at college. Right out of that, I got married – aged 22 – and came out to LA because I wanted to write comedy for television. There were no courses on that sort of thing in those days and I knew I couldn’t just get a job writing TV right away. I had to figure out what a producer does, how a writer writes scripts – how do you do that stuff?

While I was doing that, I started writing advertising copy and anything else I could! We did the writing and design for brochures and things. But it was good because we’d come up with an idea and put together a prototype of what the game might look like. We ended up designing stuff for other game companies as well as our own games. We did a game with the author of The Peter Principle, and another with the American humorist and talk-show host Steve Allen.

And you touched on this earlier, Jay… You had an extraordinary as a TV sitcom writer. Tell me about that.

Actually, I have to thank the British for a lot of that because my big break was the TV series All in the Family, produced by Norman Lear. All in the Family was a riff on the British sitcom Till Death Us Do Part… It gives credit to the writer Johnny Speight right up front. Are you familiar with Till Death Us Do Part?

Yes: Alf Garnet! Extraordinary sitcom character; terrible bigot… But unshakeably sure of himself.

Right. I’ve seen the British version – he was a bigot; that’s a good word. There’s quite a big difference between the two shows, but All in the Family’s main character – Archie Bunker – is also a bigot. A lot of the humour in the show comes from his being surrounded by people that are more liberal. After All in the Family, I worked on other shows. There was a spinoff – The Jeffersons. I also did a show called Dear John – also based on a UK sitcom.

Would that be John Sullivan’s Dear John? Very overlooked in the UK.

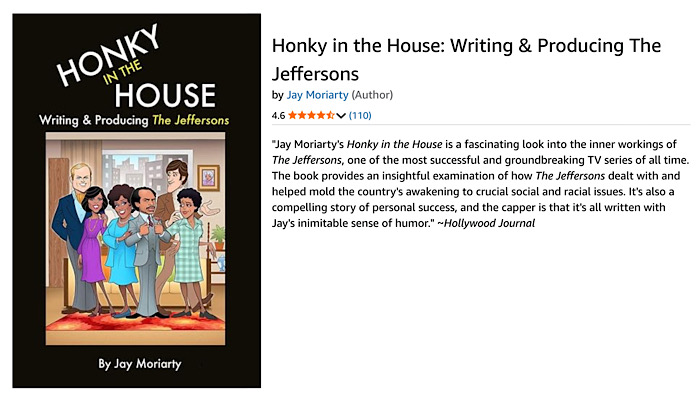

Actually, I don’t know! It was a big sitcom over here… The main actor was Judd Hirsch from Taxi. Anyway, that was based on a British show, and I did the US version of One Foot in the Grave. If you’re interested in all of this stuff, Deej, I’d be thrilled to have you read my book…

Oh, I’d love to. What’s that called?

Well, there’s a context for this! The very first freelance script that my writing partner – Mike Milligan – and I ever wrote for TV was an early episode of Good Times. To clarify, Good Times – also developed by Norman Lear – was the first American TV series to feature a black family. That was in 1974. But The Jeffersons, which came out in 1975, was the first time viewers saw an upwardly mobile black family.

I was always proud of the fact that our first staff-writing job was with The Jeffersons. The book I wrote is a memoir of how I got started and my time on the show. I often say I spent so much time with The Jeffersons that I might as well have lived with them! So the book is called Honky in the House: Writing and Producing the Jeffersons.

Honky in the House! Well, I’m glad you gave me some context! And I suppose, in the days you were writing those sitcoms, you faced – as Jonnny Speight did – criticism for putting a bigot on TV from those that didn’t see the character was being used to raise issues…

Yes, that’s partly why I liked the word honky in the title of the book. The first time I heard that word, I was in a Jesuit High School – all white students. This was in the 60s. To the credit of the Jesuits, they had a young black man come to talk to the class. He mentioned that – growing up in the 50s – he never saw anybody that looked like him on a TV screen… Except if he’d been watching Tarzan. He said, “I’d be watching the natives chasing Tarzan through the jungle, and I’d be yelling, ‘Look out, Tarzan! They’re right behind you!’ later, I realised I should’ve been yelling, ‘Get that honky!’…” That always stuck with me.

Ha! Well, what an extraordinary career. We do need to start wrapping this up, Jay. Just quickly, though, you mentioned some variations of 221B Baker Street. Was one of those with a Time Machine? I have that in my notes…

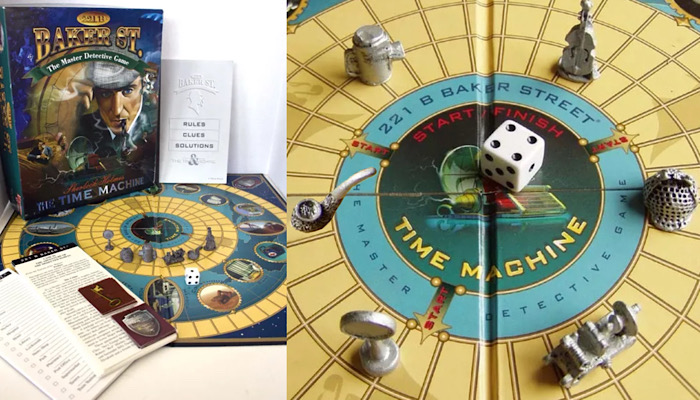

Yes! I did a spin off called Sherlock Holmes and the Time Machine. We did that in the late 80s and it’s still out now. In fact, that outsells the original in Brazil. The basic premise there is that Sherlock Holmes and Watson know H.G. Wells! They use his time machine to travel to the 20th century to investigate great unsolved mysteries: Deep Throat, Watergate, the Lindbergh kidnapping, the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa… So it’s Holmes in different times looking at real cases.

Amazing. Well, this has been really insightful – thanks, Jay – and here’s to the next 50 years of 221B Baker Street! Congratulations again.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here