Pablo Clark discusses the six-year development journey behind the game design – and art – of The Old King’s Crown

Pablo, it’s great to connect. To kick us off, for anyone new to The Old King’s Crown, how would you pitch the game?

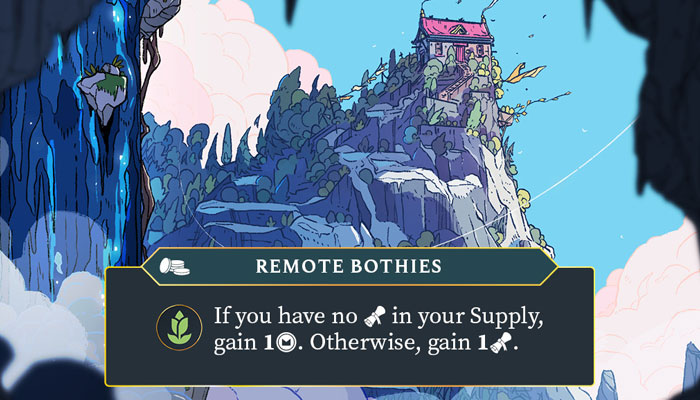

The Old King’s Crown is a big, sprawling strategy game set in a fantastical, crumbling, overgrown kingdom. It’s a big box that encourages experimentation and celebrates getting creative with the game’s systems – all backdropped by a hand-illustrated world, many years in the making/drawing.

The game pits four different factions against each other, each with differing identities and ideas about what kind of crown the next one should be – rewarding players who want to explore their intricacies and inviting you to consider different ways of approaching each session. I also think it’s a game that wants you to look up from your own plans and consider those of your opponents… Navigating fog-of-war, bluffs and countering manoeuvres are at the heart of it all.

I hope it’s a game that invites players to hang out with its world, ideas and strategies, and – I hope – in turn, it becomes richer and richer each time you visit.

What sparked the initial idea for the game?

My girlfriend at the time and I were off on a camping trip in the highlands of Scotland and we wanted to take a game with us, so I made one. The first ever version was designed to be played with a deck of cards and minimal other pieces. We played it a whole bunch by torchlight. Fundamentally, I wanted to make a card game where controlling your supply of cards was pivotal and one that encouraged feints, bluffs and brinkmanship deep down its core – where getting a read on your opponent was incentivised, almost poker-like.

Initially, it was very abstract. This let the idea live on a foundational level. Then, as it became more expressive and sound, the system started to speak for itself and advocate for what it might say thematically.

From a humble card game to this expansive version seems like a huge leap!

Yes, but even in that early design, a lot of the bones of the final game were put in place: you were forced into conflicts each round and knowing which ones to commit to, and which to concede, was pivotal. There were three regions to clash over. You could install cards in a court, and whenever you ran out of cards you would be punished with attrition. All of that remains to this day in some form or another.

It also had a couple of early thematic hooks that carried through. It had a vague setting of warring houses in a fantastical kingdom, and places like castles and necropolises played a major role. So much so that very early versions of the game were simply called Necropolis.

All that being said, I grew up often surrounded by the countryside and old ruins. Woods and fields, overgrown lanes and ancient buildings in the distance or over the water… A lot of that definitely seeped in and informed what the game, and its world, would eventually become.

The artwork in the finished game is stunning – and you did all of that too! Did the world of the game – and the artwork – ever steer design decisions? Does one inform the other?

Thanks, that’s very kind. And yes, the art and the game design definitely informed each other. What’s so interesting and rewarding is working on a project like this, where the art and design are made in tandem. On a lot of projects these steps are fairly separated, often by necessity, as a game’s art team is typically brought in the latter stages to keep art budgets focused and manageable. I had the privilege – paid for in lots of unpaid overtime! – of being able to take my time with the art. It allowed both it and the game’s design to grow up together, so to speak.

It took me a long time to find the art style for the game, as I experimented a whole bunch with different approaches. Throughout all this, the studio’s co-founder and the lead graphic designer on the game – Andrew McKelvey – was there to bounce ideas off and discuss what we were trying to achieve. We wouldn’t have been able to spend this amount of time exploring had it not all been ‘in-house’.

Regarding how the illustrations informed the game itself, I think that’s subtler. It certainly helped with faction-design, as the more we established the look and feel of a faction, the more we were able to use that as gentle guiding cues for how they might behave through their abilities. The two sides of the project acted as a north star for the other.

I understand the design process took six years…

Yes, it has! A long time. Surreal really. Though, for a portion of that, we worked on it purely part-time. I’d finish my day job and then draw and hold playtests in the evenings and at night, then again early in the morning. Long, weird hours that, over a long period of time, started to allow the game to coalesce.

What were some of the biggest development decisions you had to make during that time?

The decision to make the board an all-singing, all-dancing centre-piece that takes the players through the game felt like a big shift in how the game felt on the table in both presence and experience – it finally felt worthy of the scale we wanted to communicate with the game.

Also, the decision to make the game a set number of rounds instead of a threshold felt, on the surface, fairly slight, but actually transformed the experience, making it a leaner and more welcoming one. I think also the decision to move away from a keyword system to an icon-based one was really valuable in streamlining the amount of information we asked our players to retain.

On the whole, the game has morphed over time, but as a result of that time, it has felt like a more subtle and gentle morphing as opposed to big swing moments.

You also collaborated with Leder Games’ Cole Wehrle while finessing the game. What was that experience like? And how did that help shape the game?

It was a wonderful experience that absolutely ended up shaping the final version of the game. It all came about quite organically. We had, at that time, been working on the game for a while and we were beginning to consider where we wanted to take the game. I had been talking to some of the Leder Games folks on social media, including Cole and Patrick Leder, and they were just the nicest guys. They offered to take the game and spend some time with it and give us their feedback and suggestions, which, as a massive fan of their studio, felt like an absolute no-brainer.

They took a prototype copy and played and played and played it… What a dream – what a terrifying dream! Some of the most influential folks in board games hungrily picking apart your game!

Ha! But it went well!

Yes! Luckily, they didn’t break it, and instead they came back with a load of astute insights that really helped inform the next stage of our development. Their advice was incredibly important to us then and still is now.

You left your job to pursue the idea – what gave you the confidence to do so?

I think any decision like that is a bit of a leap into the dark. You pack up your essentials, strap them to your back and step off into empty air. In this case, we had good early indicators that our first campaign would do well enough that I could shift to a full-time role, in turn allowing me to eye-of-Sauron-focus my entire wretched will on the project. However, it was all still projections. The campaign was still some time from launching. There’s that leap into the dark. A leap I’m ever so glad to have taken.

Absolutely. And an expansion has been announced. Do you see this as a ‘sandbox’ that could spark future editions and spin-offs?

Well, now that would be telling! I will say, we definitely want to do more stuff in the world of The Old King’s Crown and there are plenty more tales we’d love to tell in time. I won’t say too much more just now, but watch this space.

Nicely teased! And, as a first time designer, do you have advice for anyone else embarking on their first game concept?

Embrace learning. Reach out to people, ask for advice. Don’t be afraid to rip and tear and begin again. Good ideas are easy, making things is hard – and that’s okay. Don’t rush, don’t skip, don’t use AI. Square yourself against the task. You’ll learn, get better and in turn that will inform not only what you are making now but in the future. Finally, don’t conform. There’s enough established folks doing that. You’re new, you’re hungry and weird – grip that and run with it.

Last question! What fuels your creativity? What helps you have ideas?

I like hanging out with the puzzle of making things. I spend a lot of time looking inward – outwardly I’m sure I look like I’m in a daze! I like to hold ideas in my imagination and turn them over and around; it’s really thrilling. I really love that feeling of knowing there’s something there and you’re bringing it to life in your head.

Oh! And graft. Don’t wait for inspiration. Go digging for it. If I have no good ideas, I’ll practise and draw or design until I have the shape of one. I don’t sit around waiting for lightning to strike – who has time for that. Get in the dirt, get your hands buried, and start shifting those lumps of clay.

Great advice. Pablo, a huge thanks for taking time out to chat and congratulations on The Old King’s Crown. Worth mentioning too that The Old King’s Crown will be returning to crowdfunding on Gamefound soon, and is available to retailers through Zatu Distribution.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here