Meet The Man that Made Monopoly: Philip E. Orbanes interviews Robert B.M. Barton†

Introduction by Mojo Nation

As celebrations for Monopoly’s 90th anniversary shrink in the rear-view mirror, we’re thrilled to present this piece by Philip E. Orbanes. Widely known as Mr Monopoly, Philip here shares details of previously unpublished interviews with Robert B.M. Barton…

Robert B.M. Barton was president at the already inveterate Parker Brothers when he initially rejected the idea for Monopoly. But after playing an early version, Barton acquired the rights – and made it one of the biggest selling games of all time. Now, as we near the 31st anniversary of Mr. Barton’s passing, Philip E. Orbanes shares their conversations.

Background by Philip E. Orbanes

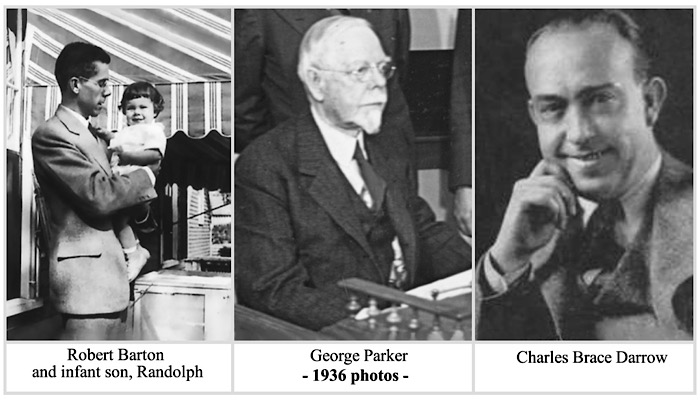

As an employee of Parker Brothers, my introduction to the former president, Robert B.M. Barton, came via his son Randolph in the spring of 1983. Randolph, more commonly known as Ranny, was – as the firm’s current president – hosting a very special event. Held at the Radisson Ferncroft Hotel in Middleton, MA., we were celebrating a doubling of our business in just one year…

This remarkable achievement was thanks to our entering the video game business the prior year. Randolph – while always successful at achieving the firm’s annual sales and profit plans since his elevation to president in 1974 – had lived in the shadow of his father’s achievements.

Among these many achievements, the elder Barton had taken the helm of Parker Brothers during the Great Depression, led the family business through several wars, saved it from bankruptcy, licensed Monopoly, acquired many other enduring games – like Clue, Sorry and Risk – and, just prior to his retirement in 1968, sold the firm for a king’s ransom to the food giant General Mills.

In any case, when the fad of handheld electronic games waned in 1981, Ranny – to his credit – backed me and funded development of video game cartridges. I was the recently promoted Product Development Vice President, having joined Parker three years earlier as a director. The first two carts – Star Wars and Frogger – launched in 1982, and both sold in their millions. So here we were at the Ferncroft, reprising 1982’s glory and premiering our expanded line of video cartridges for 1983…

After the formal presentation ended, I spotted Ranny talking with his parents, standing in the back of the theatre. Robert Barton was then 80 years of age. His wife Sally was 76. Both were tall, gray-haired and lean. Robert, bespectacled and dressed in a tailored navy suit, stood ramrod straight. He reminded me of the actor Jimmy Stewart, with an added air of dignity. Ranny formally introduced me…

Clearly, though, this was not the occasion for me to ask Robert questions. It was only appropriate to let him know who I was and my R&D role at Parker. Ranny informed his father of my influence on this celebration. He also noted that I had become the judge at Monopoly championships. Robert acknowledged politely.

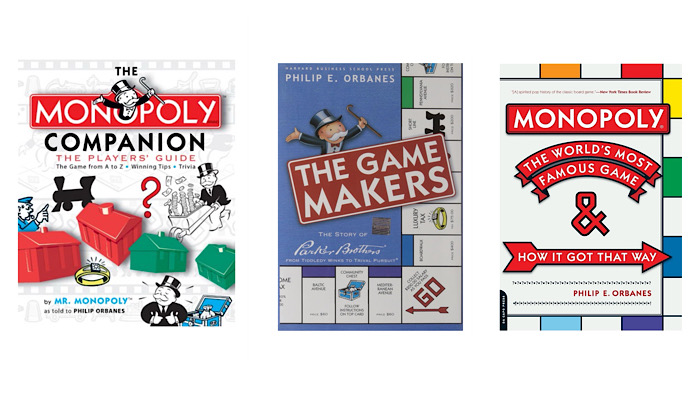

Five years would go by before I spoke to Robert again. By January 1988, I had secured the publication of my first book, The Monopoly Companion. For this, I wanted to verify some facts that only Robert could vouch for… By then, Ranny had retired and the father-son team had established an investment firm, Corn Bay Associates, to manage the family’s investments. Ranny arranged for me to interview his father at their office nearby. Eventually, we would meet four times in 1988: on the 8th and 9th of January, the 13th of October and, finally, the 1st of November.

Ahead of that first meeting, Ranny cautioned that his father was not going to give up anything until he decided, for himself, that I was genuine in my interest in his past and could be trusted with his ‘revelations.’ He was, after all, a former attorney descended from five generations of Virginian lawyers. In time, my patience and perseverance would pay off. Upon my arrival on January the 8th, I began gently with show and tell…

I brought with me the initial five Parker editions of Monopoly and asked him if he could date them in order, and also how many he recalled making of each. Barton provided answers as he studied the row of games I’d set out on a table in his office. The four ‘small box’ editions – the ones that came with a separate game board – appeared to be identical, excepting the small legal line beneath the MONOPOLY title.

He pointed. “The first is this one… The Trademark edition.”

“How many did you make?” I asked.

“Likely 10,000. It was the one we got started with and we got it into the market pretty quickly. I’d say June of ’35.”

“Which came next?”

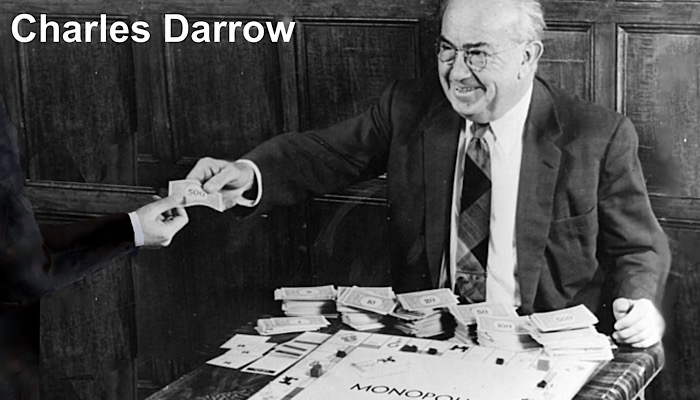

Barton rearranged the editions in order of introduction and provided a comprehensive answer: The second was the Patent Pending Edition, issued as soon as Parker’s attorneys had completed a design patent application on behalf of Charles Darrow.

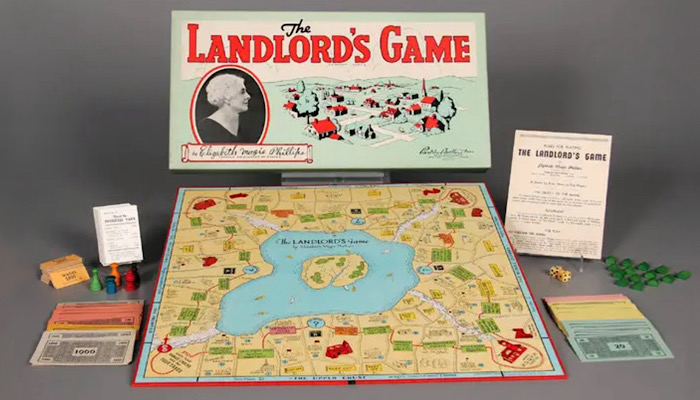

It’s worth noting that there’s a difference between mechanical patents and design patents. Design patents are like glorified copyrights… They protect the look of something, and Darrow’s ‘look’ for Monopoly was his own, whereas the game idea itself had originated with Elizabeth Magie Phillips. Meanwhile, mechanical patents protect how something works…

Barton explained that the average person doesn’t know the difference. If they should see ‘patent pending’ on a product they assume it’s a mechanical patent belonging exclusively to the owner – a misconception that manufacturers rely on. Barton thought about 50,000 were made of the Patent Pending edition.

The third box featured the ‘Single Patent’ – the number acquired from Elizabeth Phillips in November of 1935. Hers was for an earlier design patent on the look of her Landlord’s Game. Parker’s attorneys felt it wise to own it. Barton’s father-in-law, Geroge Parker, knew Phillips from prior game licenses; he had gone to Washington DC to make the deal. Barton estimated over 100,000 for this set.

The fourth game was the ‘Dual Patent’ edition, which included both the acquired patent number and the newly issued Darrow patent number. This began production in December. Ultimately, it would be produced in great quantities, perhaps a million sets according to Barton, although only the first of these were shipped before the end of 1935. The total 1935 Monopoly production, according to Barton, was “A bit north of 250,000 units.”

The fifth edition was the ‘Deluxe’ set which came in a large white box. It was a replica of the initial set Darrow had sold to department stores in Philadelphia. Barton estimated that this edition got into production in late June or July of 1935 and its first run was “likely” 5,000 pieces although it would go on to sell many, many more.

With the 1935 production of Monopoly covered, I turned to 1936 and how Barton had managed to produce over 1,800,000 sets. I relate what he told me in my book Monopoly: The World’s Most Famous Game. The next day, I returned with a prepared list of new questions. Having found favour with our first session, Barton answered these without hesitation or calculation.

What was Charles Darrow’s profession before Monopoly enabled him to retire early?

A heating Engineer.

How did Darrow react when you learned he had not invented Monopoly? Did it strain your new friendship? Was it difficult to reach a more reasonable agreement with him in light of other claims of authorship?

I had earlier learned that Darrow took an old idea and gave it life and a new name. This is where most new games come from. Darrow is the father of Monopoly and it is his look. He was amenable to a lower royalty in return for Parker absorbing whatever legal problem came along. We went after a few who tried to cozy up to Monopoly.

When you purchased Monopoly from Darrow in early 1935, what became of his recent ‘black box’, small edition inventory?

Darrow had made 7,500 sets of his new edition, at the suggestion of his retailers. He only took receipt of them a month or two before we licensed his rights, Consequently, I agreed to buy his remaining inventory, likely 5,000 odd sets, fill his open orders and extract whatever parts we could to use when manufacturing our first sets.

How soon in 1935 did Parker Brothers start to ship its game? I believe you said it was in late spring?

Yes. As soon as we received Darrow’s stock we began conversion and reissue, which took a little time.

Did Darrow leave Germantown, Philadelphia, and buy his farm in Ottsville, PA soon after selling Monopoly to you? Or did he wait a few years?

His purchase came a year later, sometime in 1936, when it was apparent he could afford to retire.

Aside from the game Finance, did anyone else try to claim prior ownership in Monopoly?

I purchased Finance, of course. So no issue there… But about a year later a man in Reading, Pennsylvania, wrote a letter to Time saying that he and others had played Monopoly at the University of Pennsylvania years before. I went to Reading to investigate his statement and found that, indeed, a kind of real-estate trading game had been played at the university. It did not have Darrow’s format, nor was it called Monopoly…

That worthless fraud, [Ralph] Anspach, accused me of getting the Monopoly trademark by fraud. In fact, the top leading Boston trademark attorneys got it and maintained it for us perfectly legally. Every judge, including the trial judge, agreed that I had a right to feel outraged [by Anspach’s claim] and Anspach withdrew all charges of fraud. He then used clever attorneys to try a different attack to try and strip Parker of the rights to make our game exclusively, so that his trademark-violating version could survive. We know the outcome of that one and General Mills’ decision to settle, which I most certainly would not have done.”

——-

I asked Barton to tell me what he did to save Parker Brothers after his arrival in 1933, and before Monopoly took the country by storm. I suspected he would like recounting this success story – and I was right. He talked without much pause and I only had time to write down the facts he related, which would form the basis of pages 78-94 in my 2004 book, The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers, and pages 63 to 82 of my 2007 book, Monopoly: The World’s Most Famous Game.

There was, however, a topic near the end, which Barton himself raised. Namely, Charles Darrow’s son who was intellectually challenged. Barton mentioned it when speaking about his admiration for Darrow, who had to commit son Richard – known as Dickie – to an institution in Vineland, NJ., before Monopoly made him rich and when he was scraping for money. I took note of this because I knew Vineland well. I had grown up 30 miles to the south and my parents often shopped in the many stores on its main street, Landis Avenue. I decided not to mention this topic in either of my subsequent books. Two questions near the end caused him to stop and think before answering…

How was it for you to make the jump from Virginia to Massachusetts, and to go from your father’s law practice to running your father-in-law’s company?

The first was effortless because I had gone to school at Harvard. I was quite comfortable in Boston and surrounds. The second was difficult. I knew nothing about running a business other than what I picked up while representing clients engaged in commerce, I fell back on principles of conduct that worked for me in law and especially the core ideas taught to me by Mr. Parker… His list of twelve. I’ll tell you about them the next time we meet.”

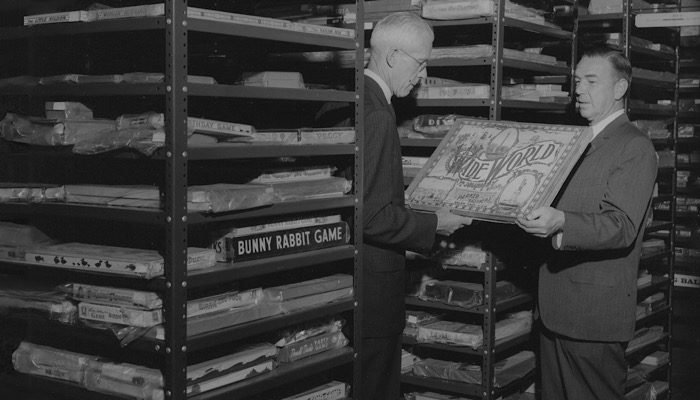

Life intervened and I didn’t see him again for several months. That fall, we both had a chance to regroup. My main topic this time was his recollections of ‘Mr. Parker.’ Robert had a lot to say, and his information is found in my Parker and Monopoly books, from 2004 and 2007.

Of note, he took me through Parker’s core business principles. These struck me as significant and I decided to use them as the theme for chapters in The Game Makers. Barton started by saying:

Now understand, Mr. Parker did not attend college, He could have – he was gifted, of course. But business called him and his older brothers encouraged him, and after he recovered from an illness while working at a newspaper, he opened his own firm. He had a lot to learn. He may have been a fine game inventor and a very effective salesman of his products, but he couldn’t judge people, or balance a ledger, or plan a production line. But he learned and every time he figured out a principle that worked, he applied it diligently thereafter.

I’ve interviewed some Parker veterans who knew George Parker in the 1930s and 1940s. Some venerate him. Some think he was stuffy and acted like a king. How do you reconcile these observations?

I can appreciate the dichotomy. Having been president for many years, I I can explain… Mr. Parker always regarded his employees as part of a large family. He had a kind heart – a very kind heart, which sometimes pained him and got him in trouble. By that I mean if he learned one of his people had a personal setback, perhaps an illness or maybe a house fire, he would call that person into his office, ask how much money was needed, and issue an IOU, which the employee signed…

Mr. Parker did not specify repayment terms because, frankly, he did not intend to collect. Well, some workers upon hearing of his loans, would plague him with phoney tragedies. But Mr. Parker caught on and would have others verify an employee’s needs before issuing a loan an IOU. Thereafter, he adopted a more standoffish, haughty demeanour to put distance between himself and those he knew were too clever for their own good. By the way, he never collected on any of his IOUs. I found them in his desk drawer after he died. Enough said.

Were his business principles sound?

As I mentioned, there were twelve in all, settled upon over many years. They were quite sound. Textbook quality but honed by actual experience. His genius was to equate the strategy of winning a game to those of running a successful business. I couldn’t have made this discovery. He was a born gamesman; I was a mere attorney.

I see his game analogy, based on the list you gave me. Like Number One ‘Know your goal and reach for it,” or Number Three, obviously, ‘Play by the rules but capitalize on these…’

And “Bet heavily when the odds are in your favour.”

You especially applied that one when you put all the company’s resource into satisfying the insane demand for Monopoly in 1936, right?

Had to…

——-

During our fourth and final session, I had more questions about Monopoly and Mr. Parker. Our discussion became free form; relaxed, and I had to scramble to take notes. I built his input into The Game Makers as well. Before our time ran out, I had a chance to ask him about Clue and Risk, the other big hits published under his watch.

What did you think of Clue when it arrived?

It wasn’t called Clue then. Norman [Watson] and his team in Leeds called it Murder which made us very apprehensive. But we owed Waddingtons a great favour for spreading Monopoly throughout Europe and so we decided to play the game.

How did you like its play?

We liked it: pure and simple and clever. Just the right amount of thought was required, but we didn’t think parents would want their kids playing a game about a sin.

So you changed the name Murder to Clue?

Correct. And we decided to acquire the license for Sherlock Holmes and call Clue a Sherlock Holmes mystery game. You see, we felt putting the emphasis on making the players detectives who were solving a dastardly crime would be seen as upright.

How did it sell?

The trade held their breath, but it sold right from day one. After a few years, we realised we didn’t need Holmes anymore. The game was here to stay. So Norman, who was still beset by materials rationing, decided to publish it at Waddingtons by shifting from another game’s stock of paper and so on. Clue soon became international – except he decided to call his game Cluedo.

What about Risk and the theme of conquering the world?

This one came from our other European partner, Miro, in Paris. We were somewhat hesitant because it was the Cold War and things were heating up. War games were not in vogue with our market.

How about its play?

Its core was fine, but the game took much too long to play, until Eddie Parker [founder Edward Parker’s grandson] solved that.

How so?

He made each set of cards turned in yield more and more armies. It escalated until one player was able to sweep the map.

Was it called Risk when it arrived from Miro?

No, it was The Conquest of the World, or something like that. One of our salesmen came up with the name Risk. We liked it immediately. Turns out, the letters r-i-s-k were the initials of his four grandkids. That’s true!

Risk was expensive. All those pieces and large board. But as a seventh grader, I couldn’t wait to get one… I couldn’t stop playing it after I did. Were you worried about cost?

Certainly. We had to break a price ceiling with Risk. Our advertising agency decided to emphasise the high price in our TV commercial. Turn a negative into a positive. Brilliant idea that worked. Oh, and we purchased the wooden pieces from Czechoslovakia, behind the Iron Curtain.

Our meeting had to conclude as Ranny was pulling his father out the door to a financial meeting. That, as it turned out, would be the last time I would see Robert Barton. He passed away aged 91 on February 14, 1995. He is buried at Waterside Cemetery, Marblehead, Essex County, Massachusetts, USA.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here